Catalogue d’Oiseaux

Pierre-Laurent Aimard hardly waited for the applause to stop before attacking the grand piano with his long fingers. The opening trill in the upper registers was made up of a disorienting scuttle of notes, followed by ominous metronomic bass steps walking slowly up the keyboard. There were rests, pauses and uncomfortable silences. This was Olivier Messiaen’s La Buse variable (the buzzard).

Then came jazzy chords and luscious major phrases, then staccato chops, runs and stabs. The wit of a bird’s movement as well as its vocalisations filled the room. There was bird presence – a vital, pulsing, electric atmosphere made from the vibration of piano strings. What? Was that a fist just now to the bass notes of the keyboard? Aimard’s interpretation of the next piece, Le Merle bleu (the blue rock thrush), was ferocious and sometimes threatening with the bashed big strings left to giddying resonance and decay.

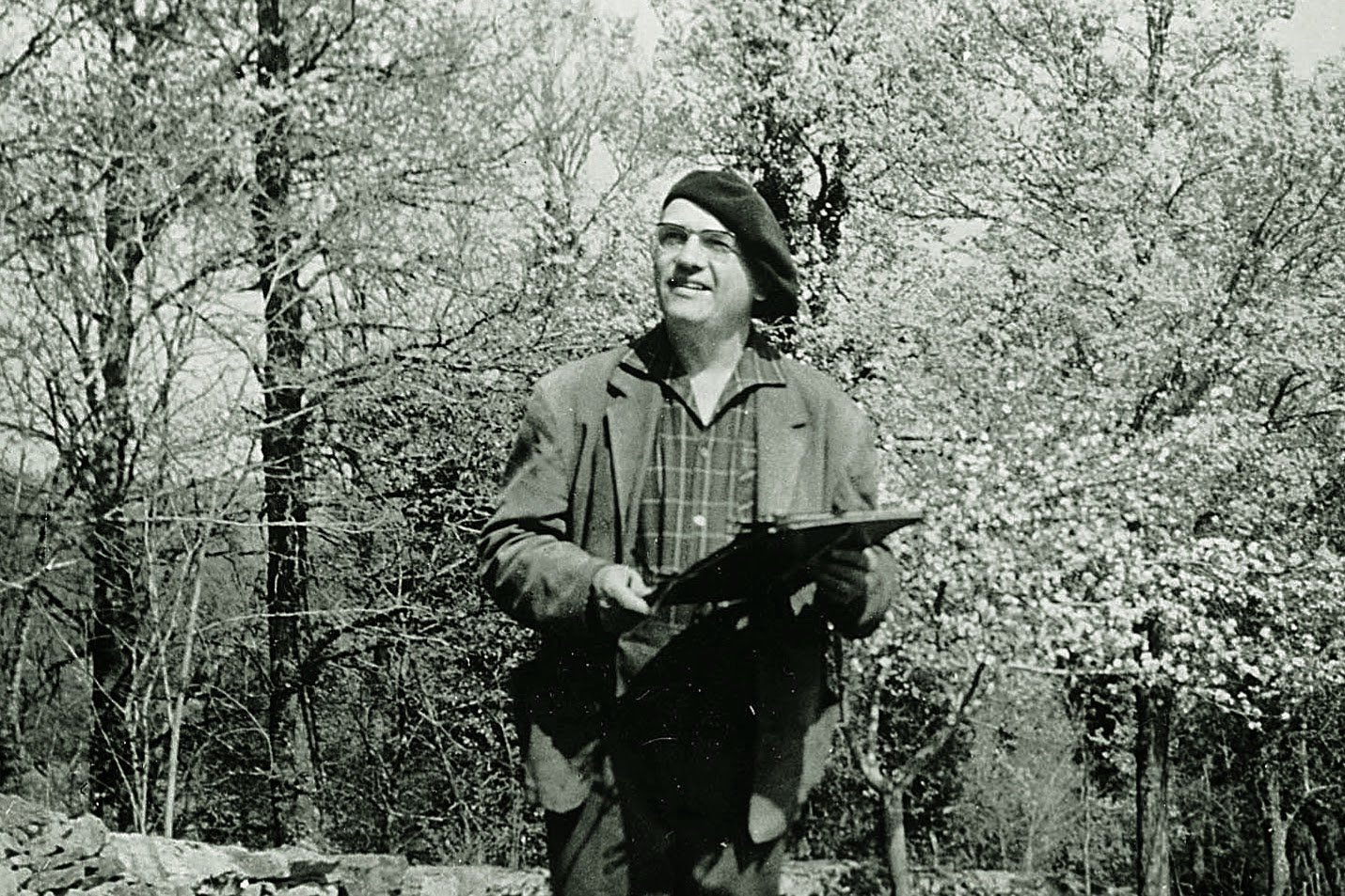

This inadequate account of a performance of Messiaen’s Catalogue d’Oiseaux is the best I can do. The work, which is an almost-three-hour-long piano cycle of thirteen pieces each named after a principal bird, was the result of decades of listening to the character of natural environments. ‘I am an ornithologist’, said the composer. But Messiaen’s Catalogue d’Oiseaux is so much more than an attempt to collate the songs of these species and the 64 others that appear in the music. Messiaen began transcribing birdsong as a teenager in France and then put the notes to work in his compositions as a prisoner-of-war in Germany. During the 1950s the rhythms, tones and melodies of birds and their habitats took over his musical thinking. To fit the bird songs into his existing tonal schemes, Messiaen made them lower and slower, expanding their microtonal intervals, and devising complex ‘chords of resonance’ to mimic the tone-colours of individual species.

Yet, the pieces he wrote were not attempts to reproduce birdsong (though his transcriptions from the field were as precise as anyone had rendered in musical notation). They were an evocation of his sensory impressions of the French provinces he immersed himself in – as well as the soundscape, Messiaen accounted for the land forms, colours, perfumes and weather, during the day and at night. He found the ‘true, lost face of music somewhere off in the forest, in the fields, in the mountains or on the seashore, among the birds’. With Catalogue d’Oiseaux he set out in music the ecologies of the French regions he loved. Messiaen took the oldest of musical motifs from the natural world and made them rivetingly modern. He went far beyond what had been done by Beethoven or Vaughan Williams.

In his earlier chamber piece Quartet for the End of Time, the first movement has the clarinet and violin exchange sounds from blackbird and nightingale, but the solo clarinet in the third movement is a musical attempt to link the boundless enthusiasm of singing birds with the long, dark weight of eternity. ‘The birds’, Messiaen wrote in his note about the piece, ‘are the opposite of time. They represent our longing for light, for stars, for rainbows, and for jubilant song.’ The world of birds gave intense meaning to his Roman Catholic faith. The world of birds reflected the constancy of the universe, of life, of the generations. These ideas reigned over his music to the end.

+ + +

Pierre-Laurent Aimard played La Buse variable (buzzard), L’Alouette calandrelle (short-toed lark), Le Loriot (golden oriole) and Le Merle bleu (blue rock thrush) at the Britten Studio, Snape Maltings, Aldeburgh on 19 June 2016, as part of the song cycle of all thirteen movements of Catalogue d’Oiseaux (1956-58).