The book

This is my first book. And the first book on the place of nature’s sounds and how they have been understood in early twentieth-century British life. I reveal the essence and composition of sounds that made up ideas of peace-and-quiet and ‘silence’, while relating them to national identity in times of war and technological change. The book highlights the early history of natural history on BBC radio, before the formation of the Natural History Unit. It shows how birdsong was seen as a essential part of British culture and even a marker of civilisation, when human behaviour was in question.

Listening to British Nature: Wartime, Radio & Modern Life, 1914–1945

Oxford University Press, 2022

Hardback, 232 pages

ISBN 9780190085537

> “In this sparkling book, Guida establishes himself as a pre-eminent listener of the past. Listening to British Nature is an important book, subtle in its telling and striking in its implications for our understanding of historical acoustemology”

“By cleverly weaving together themes of nature, war, and broadcasting, Guida offers us an exciting new way to listen to – and to understand – twentieth century Britain. His book is clearly the result of meticulous research and deep thought. But it’s also infused with genuine compassion for the people and events it describes. This is history at its glittering, exhilarating best”

Contents in detail

Listening to British Nature: Wartime, Radio, and Modern Life, 1914-1945 reveals for the first time how the sounds and rhythms of the natural world were listened to, interpreted and used amid the pressures of early twentieth century life. The book argues that despite and sometimes because of the chaos of wartime and the struggle to recover, nature’s voices were drawn close to provide security and engender optimism. Nature’s sonic presences were not obliterated by machine age noise, the advent of radio broadcasting or the rush of the urban everyday, rather they came to complement and provide alternatives to modern modes of living.

This book examines how trench warfare demanded the creation of new listening cultures to understand danger and to imagine survival. It tells of the therapeutic communities who made use of nature’s quietude and the rhythms of rural work to restore shell-shocked soldiers, and of interwar ramblers who sought to immerse themselves in the sensualities of the outdoors. It reveals how home-front listening during the Blitz was punctuated by birdsong, broadcast by a German on BBC radio. To pay attention to the sounds of the natural world during this period was to cultivate an intimate connection with its energies and to sense an enduring order and beauty that could be taken into the future. Listening to nature was a way of being modern.

Introduction

1. Birdsong over the trenches: the sound of survival and escape

‘The air is loud with death’ - listening in fear for danger

Sonic relief amid the shelling

Regenerative rhythms

Resilience and ‘carrying on’ in birds and men

Skyward escape with the lark

Conclusion

2. Pastoral quietude for shell shock and national recovery

Quiet for the wounded?

Country house therapy

The ‘beneficent alluring quietude’ of the Village Centre utopia

Quiet for national recovery

Conclusion

3. Broadcasting nature

John Reith’s public service nightingale

In touch with cosmic harmony

Normalising radio with nature

Conclusion

4. The rambler’s search for the sensuous

Re-balancing the senses

Willis Marshall: into the moors

Nan Shepherd’s merger with the mountain

A violent assertion of personality: hedonism in nature

Conclusion

5. Modern birdsong and civilisation at war

Recording and modernising birdsong

Home front listening tensions

‘Consoling voices of the air’: Ludwig Koch’s broadcasts

Birdsong civilised and civilising

Conclusion

Afterword

Bird therapy on the Western Front

Nurses with caged canaries on an ambulance train near Doullens, France, April 1918. Photographer: David McLellan (© Imperial War Museum)

Soldiers heard birds singing in the most trying conditions imaginable in the trenches. Amid the noise of artillery, the chaos of battle and the anxious moments in between, soldiers seemed to pull out of the air the musicality of birdsong. It was needed. Men wrote about it in letters home and in their diaries. It was a miraculous sound that nobody expected to hear on the battle front. But bird life carried on and this helped soldiers carry on too.

This photograph shows nurses on a hospital train showing off their caged canaries. The fluting chatter of the birds was said to cheer up wounded soldiers and remind them of home. Back in Britain, hospital wards would sometimes keep a songbird by the window. The Daily Mail in January 1916 told how Private Dobson from the Bedford Regiment had been sent a canary, which sang in the sunlight beside his bed.

Quiet for the wounded?

A banner reading ‘Quiet for the Wounded’ outside Charing Cross Hospital, London, September 1914 (© Imperial War Museum)

What was this embroidered banner doing outside Charing Cross Hospital in the first months of WWI? The incantation, ‘Quiet for the Wounded’ followed Florence Nightingale’s earlier advice for nurses to keep recovering soldiers away from noise so they could rest and heal. Yet, during the conflict few had the luxury of quiet, even if they were shipped back from the Front to recuperate at home. But after the war was over, medical and pubic opinion lobbied for the provision of quiet, leafy surroundings to help men through the shock of war. It was a sign of respect to those who had served, as well as a balm for the nerves.

The best kind of therapeutic quietude was to be found in the countryside, not in the city. Shell-shocked officers were treated in country house hospitals with extensive gardens. And, unusually, rank-and-file soldiers were immersed in the gentle rhythms of the natural world at Enham Village Centre in Hampshire (part of Enham Trust today). In fact, the whole nation needed some peace-and-quiet to allow the senses to rest and to come to terms with what had happened.

Broadcasting silence

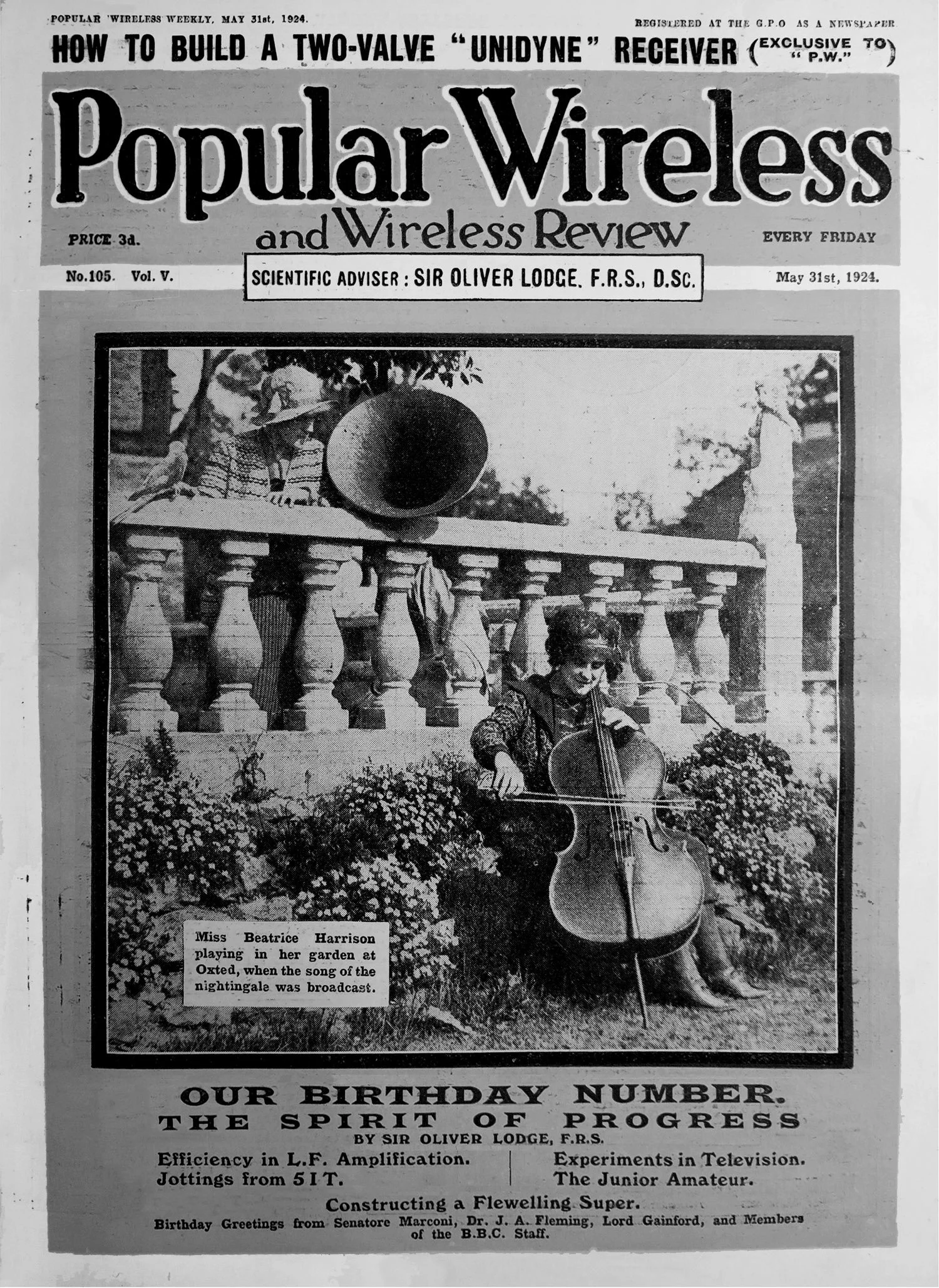

Beatrice Harrison poses with her cello in her garden in Oxted, Surrey, May 1924

The famous broadcast of Beatrice Harrison playing her cello with a nightingale in her garden was something of a media stunt. It showed that live transmissions could be made from outside of London and that novel sound events could be relayed to the entire nation. But the BBC’s chief, John Reith, was not interested in gimmicks. For him the voice of the nightingale on the airwaves was a demonstration of more-than-human culture, of the transcendence the new medium could summon from the ether. The sound of the bird in people’s front room was a kind of sublime silence that busy urbanites craved.

Dunking the senses in the natural world

G. H. B. Ward taking a dip in a pool on the Bleaklow moorland, Derbyshire c. 1910-20. Photographer: Harry Diver (Courtesy of South Yorkshire and North East Derbyshire Area Ramblers)

Rambling in the 1920 and 30s was not just a way to escape the grime and noise of urban life. It was a chance for men and women of all classes to make sensuous contact with the natural world. Each of the senses could be reactivated in a celebration of the freedom to feel. Ramblers grappled with rocks, buried their faces in the heather and skinny-dipped in pools and rivers. The sensations to be had in the hills were a key part of the hedonism of walking on offer to everyone.

Birdsong in a box

Songs of Wild Birds (1936), a sound-book by Ludwig Koch and Max Nicholson

The German sound-recordist Ludwig Koch was the first to capture the range of British birdsong on gramophone record. Of course ornithologists loved his first collection in 1936 called Songs of Wild Birds, but so did music critics. One said of Koch’s records: ‘They are worth a dozen of the music everyone knows. They are worth twelve hundred cage-birds’. These recordings were the basis of Koch’s BBC broadcasts, transmitted throughout WWII. The songs of ordinary British birds were heard as consoling voices that spoke to everyone. They were the patriotic sound of the nation, untainted by war and fear. On the radio, they became part of British culture and a civilising force for a society in crisis.